So Vybz Kartel was acquitted on one murder charge a couple of days ago. On the afternoon of the verdict, I went and spoke to defence lawyer Christian Tavares-Finson about the case. I wrote a piece for Pitchfork about it, but my original had a few extra details from the case and bits and pieces from Tavares-Finson that folks might be interested in…

Just two weeks ago, a bass-heavy, cracking tune called “Compass” by Vybz Kartel was unleashed. A sure summer highlight, given a recent lull in head nod-inducing dancehall tunes. “Keep yuh safer than ten padlock,” the man also known alternately as “Di Teacha” and “Worl’ Boss”, rhythmically repeats. This is more than a little tongue in cheek, given that Kartel has been locked up himself, waiting to face murder charges since September 29, 2011.

“Compass” was far from the first track released in the past almost two years. Though he is certainly not permitted by law to be recording while in jail, Kartel has oddly managed to be almost as prolific as when he was a free man. With explanations and hypotheses ranging from the use of old acapellas to voicing over the phone to straight up illegal activity, UK soundcrew Heatwave has provided a nice rundown of best (and worst) of the many tracks released since Adidja Palmer’s arrest. One of the best is the hit single from February 2013, “Peanut Shell.” It’s now a recent arty short film/video starring World Reggae Dance Champs Shady Squad.

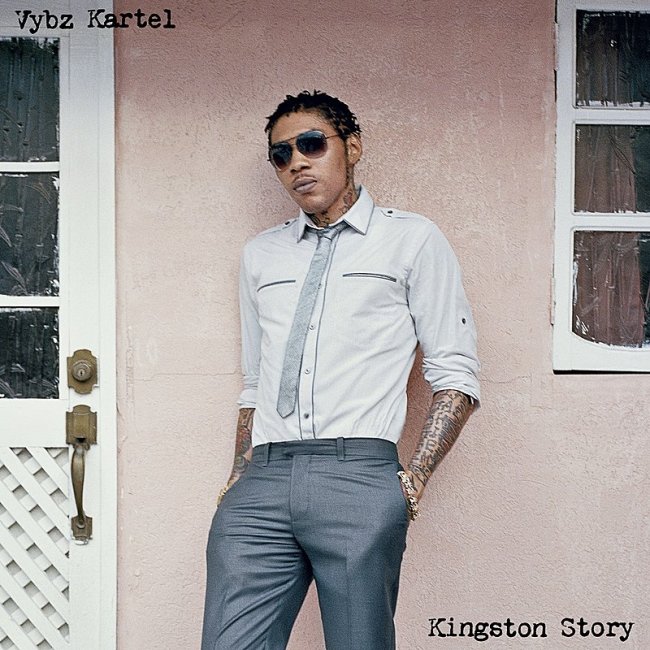

Vybz Kartel was on the rise in 2011—a critically-praised new album, Kingston Story, produced by American producer Dre Skull and a profile in the New York Times. No stranger to controversy, from specializing in explicit lyrics to flaunting his bleached skin to his public conflicts with fellow performers, Kartel has always butt heads with someone or other. His business ventures, such as Daggering Condoms and Street Vybz Rum alongside his rather racy reality tv show “Teacha’s Pet” also did little to endear him to so-called respectable society. His detractors seemed vindicated when the deejay born Adidja Palmer was arrested for two counts of murder.

On July 24, Palmer was acquitted of one of these two murder charges, exiting the courthouse and waving to a large crowd of screaming fans. In the shooting death of music promoter Barrington “Bossie” Burton, Palmer stood accused alongside two others. Though rumors of cellphone-video footage, DNA evidence, and text messages swirled in the media and online amongst fans, the case hung on witness statements that were disallowed by the judge since the police could not secure the presence of the witnesses themselves. According to defense attorney Christian Taveres-Finson, “We didn’t believe that they had any witnesses. We didn’t believe that the police were investigating the matter properly.” Sure that Palmer will be exonerated, his legal team feel that a defamation case might be in the cards: “When he comes out, we will look at [that] very carefully.”

In a post-verdict statement to his fans, the “Worl’ boss” remained defiant: “I had the utmost confidence from the outset as I knew I was being used as a scapegoat as usual because of my image and content and some of my music.”

What remains is the case of Clive “Lizard” Williams, who was allegedly beaten and shot to death in Palmer’s Kingston home. This case, with six defendants in total, is due to come to trial in November. According to Taveres-Finson, the evidence is again “circumstantial. We have the view that he shall be out on bail.” And how soon? “It will take a couple weeks to put the documents together, so anywhere between three or four weeks.”

Whether or not the bail hearings lean Palmer’s way, the artist that is Vybz Kartel is not going away soon. Nothing seems to stop his popularity on the streets of Kingston and in the minds of dancehall fans worldwide. After all, there was yet another new tune released just this week . . . there’s surely more where that came from.